In their recently published PLOS One article, researchers Christopher Barrie and Arun Frey investigate the possibility of surveying protests using only Twitter data. Using the case of the 2017 Women’s March in the United States, the research reveals new opportunities and ongoing challenges of using Twitter data for protest research. The study takes an innovative approach to identifying on-the-ground protestors on the basis of their digital activity, and estimates the demographic and ideological composition of protest crowds on the basis of users’ online activity alone. While the article makes significant advances, the study also points to persisting discrepancies between online and offline samples of protestors.

The question of who participates in protest is a crucial one for academia, policy, and public debate. Studying protest participation, however, is a complex endeavor. To survey protests, scholars often have to go to protests themselves and survey participants. But since protests erupt spontaneously, researchers rarely have the time to organize survey questionnaires, gain clearance from institutional review boards, and hire interviewers before the streets once again empty. Even if they do manage this, the costs are very high.

Given that protest and dissent are increasingly visible online, however, Christopher Barrie at the School of Social and Political Sciences, University of Edinburgh and Arun Frey at the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science, University of Oxford, propose a new method for identifying and examining the profile of protest participants.

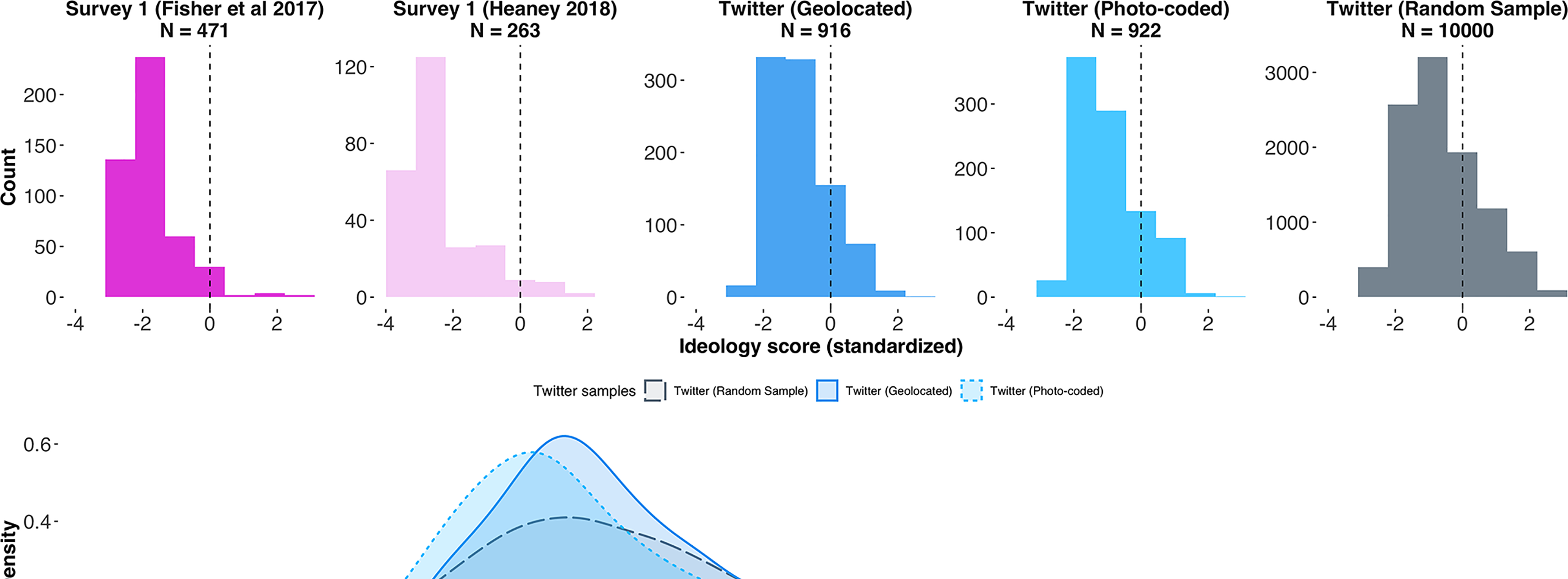

Instead of only relying on the hashtag used in tweets to generate their sample, the authors use geolocation or image data to locate individual users to the actual routes of protest marches. Using multidimensional scaling and machine learning techniques, the authors estimate demographic and ideological ideal points on the basis of users’ Twitter profiles, and compare their results to two in-protest surveys of protest participants in Washington, DC.

This is the first time that researchers have tried to ‘survey’ protestors from afar and the first time they have managed to compare samples of protestors derived from off- line samples and online—‘digital trace’—samples. Future work could automate this empirical strategy to generate data on protestors cross-nationally and at scale. This should, of course, also give us pause when considering the amount of information we can now access on sometimes sensitive forms of political action. After all, this data is accessible not only to researchers but also to governments.

In summary: this article represents a major advance. It demonstrates we are getting closer to being able accurately to infer demographics and ideological outlook of participants at political events using only information about what individuals say and do on- line.

For more information and to cite this research, you can find the open-access research at: Barrie C, Frey A (2021) Faces in the crowd: Twitter as alternative to protest surveys. PLoS ONE 16(11): e0259972. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0259972