Published in a special issue of the Population and Development Review, Dr Joshua Wilde and Jasmin Abdel Ghany provide the first dynamic birth forecast for the COVID-19 pandemic using Google search data.

The full article, ‘Digital Trace Data and Demographic Forecasting: How Well Did Google Predict the US COVID-19 Baby Bust?’, can be found in the Population and Development Review special issue.

Together with co-authors at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Dr Joshua Wilde and Jasmin Abdel Ghany analysed the effectiveness of digital trace data in predicting fertility change caused by the COVID-19 pandemic in the US.

The authors used predictions based on forecasts rather than actual results, otherwise known as ex ante predictions, since there are significant delays in the release of birth data which prevent timely analyses on the relationship between COVID-19 and fertility rates.

Instead, digital trace data in the form of Google searches was used to help predict births 7 months into the future. As well as being immediately available and free, Google search data may more accurately reflect behavioural change than a direct self-report of those behaviours.

The authors made the ex ante prediction on the future of US fertility as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic in October 2020, well before the birth effect of the pandemic could have possibly been known. They did this by using 19 years of birth data across 51 geographic regions, or 9,792 possible state-month-year observations, and pregnancy-related Google search data.

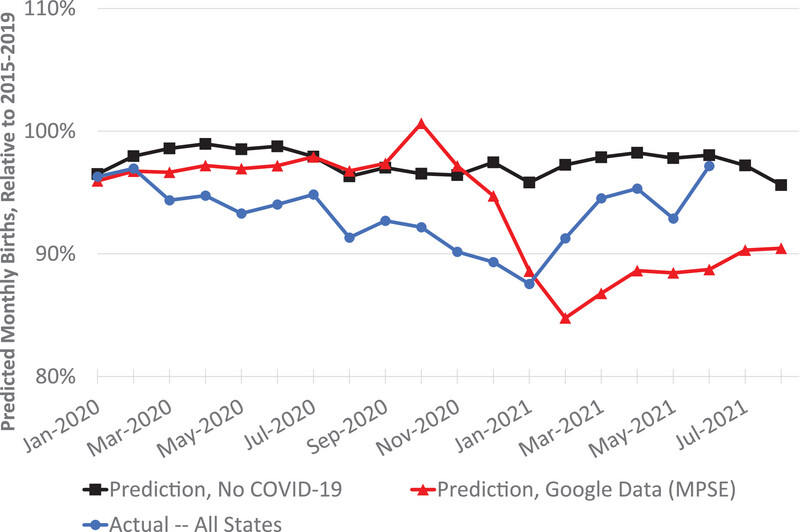

The ex ante prediction was that monthly US births would drop sharply by approximately 12% between November 2020 and February 2021, and then begin to rebound while remaining depressed through August 2021.

Current Google search volumes for various keywords relating to conception, pregnancy, childbirth, and economic stability were primarily used for the study’s forecasting model. The analysis found that peaks in keyword searches related to conception and pregnancy were associated with higher numbers of births in the following months at expected time lags, and highly predictive of births.

Excess searches for “Morning Sickness”, for example, were associated with more births 7 months later which is roughly consistent with when morning sickness most often occurs. Including information on keyword search volumes also significantly improved forecast accuracy over a number of cross-validation criteria.

Another strength of using Google search data was its effectiveness in improving prediction accuracy during crises. These predictions were also heterogeneous in understandable ways, with characteristics associated with lower socioeconomic status, larger minority populations, and more COVID-19 cases per capita showing larger predicted birth declines.

Study figure 4: US births by month: predicted versus actual

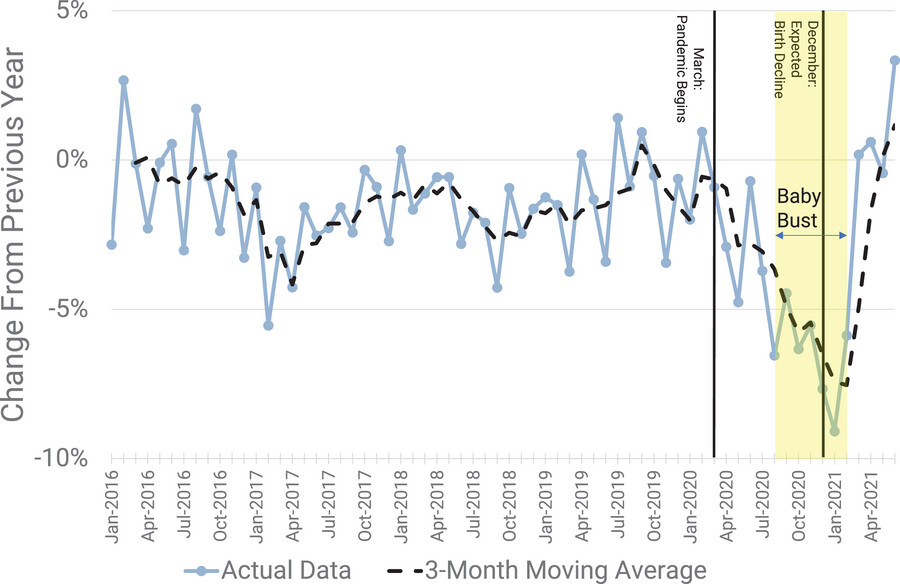

While the predictions were generally accurate in terms of the magnitude and timing of the eventual realised birth declines, there were important misses regarding the speed at which these reductions materialised and rebounded. Births began deviating significantly from the prediction almost immediately after the beginning of the pandemic, and there was a faster than predicted birth rebound in the spring of 2021 – with a breakdown in the fundamental relationship between searches for unemployment and births after just a few months of the pandemic.

Study figure 5: 12-month percentage change in births, 2016–2020

Another limitation of using Google search data is that it can only predict fertility change 7-10 months in the future at most, leaving the long-run effects unknown.

Jasmin Abdel Ghany, co-author and DPhil student at the Leverhulme Centre for Demographic Science and Demographic Science Unit said, ‘We hope that this unique evaluation equips demographic researchers with a starting point to address the strengths and weaknesses of using digital trace data to predict fertility changes.’

The study concludes, ‘This rare ex post evaluation of a real-time ex ante prediction serves as a powerful demonstration that digital data can indeed be used in forecasting, significantly improve model forecasts, and be useful indicators of population behavior; yet they are not a panacea for traditional problems of scare data and forecasting error as many would hope.’

This article is part of a special edition of the Population and Development Review which also features an introduction co-authored by Dr Joshua Wilde that investigates the lessons learnt in studying fertility and family dynamics in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The full article, ‘Digital Trace Data and Demographic Forecasting: How Well Did Google Predict the US COVID-19 Baby Bust?’, can be found in the Population and Development Review special issue.