Unemployment affects social trust in societies in different ways, according to a recent study in Social Science Research, conducted by Dr Leo Azzollini from the Centre and Oxford’s Department of Social Policy and Intervention.

Trust in strangers, or a ‘generalised other’, is a well-established pillar of democratic societies, as it allows cooperation and solidarity at scales beyond the individual social networks.

However, this social pillar is far from stable. It can be toppled by negative macro-level socio-economic dynamics such as inequality or unemployment, but also by personal negative experiences.

In the wake of the socio-economic disruptions caused by the Covid-19 pandemic, combined negative effects may undermine democracy. Exploring the relationship between labour market disadvantage and social trust is therefore more important than ever.

The study, published recently in Social Science Research, addresses an obscure aspect of this phenomenon – the joint impact of unemployment rates at the regional level and individual unemployment experiences on social trust.

While previous studies had assessed the impact of both, this is the first to examine their interaction. The study also separates between average levels of unemployment, and their evolution over time.

Study findings

Relying on European Social Survey data for 29 countries and 227 regions in Europe between 2008 and 2018, the study finds that unemployment affects social trust in three ways:

- Experiences of unemployment decrease social trust, relatively to those that have never experienced joblessness.

-

Short-term increases in the unemployment rate do not appear to affect social trust.

-

In contrast, unemployment only matters in the long run. In regions where average unemployment was high between 2008-2018, citizens are consistently less trusting.

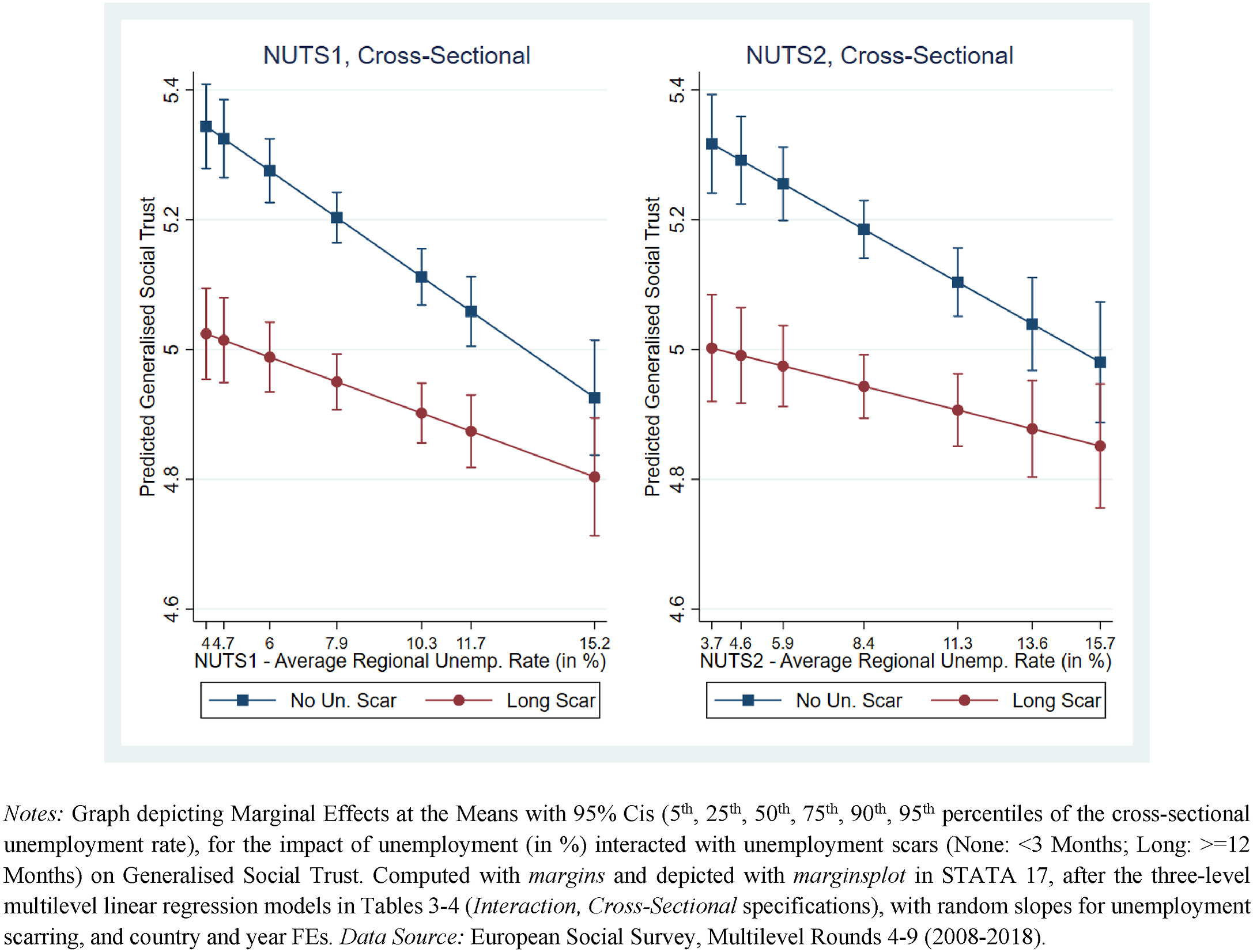

By combining individual experiences and collective dynamics, the study found that personal experiences matter only when the average unemployment rate is low (see study figure below).

On the other hand, personal job market experiences do not matter in shaping social trust in high-unemployment regions, as the collective dynamics overcome individual characteristics.

‘The findings suggest that stigma is key to understanding what is going on. Losing work can scar a person’s trust in wider society, and lead them to focus inwards. But if you lose your job somewhere where joblessness is common, it does not affect your worldview so much, as social trust is lower anyway’, says study author Dr Leo Azzollini.

The study also found that short-term unemployment variations at the regional level lacked relevance. This is crucial as social trust, at a collective level, seems only to be affected by medium or long-term economic processes.

Dr Azzollini adds, ‘This is both good and bad news – while a short-term economic recession is unlikely to shake collective faith in society, those regions with high-unemployment rates may be stuck in a “trap”, where social distrust and poor labour performance are linked. And while trust may be resilient at a collective level, those who lost their jobs are more socially distrusting even in low-unemployment regions.’

The author concludes: ‘Policy-makers need to consider carefully labour market dynamics at regional levels within countries, as the vicious circle of unemployment and social distrust may be difficult to break, with potentially dire effects for contemporary democratic societies.’